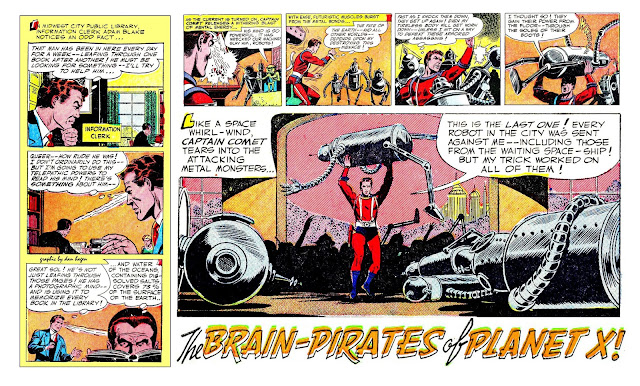

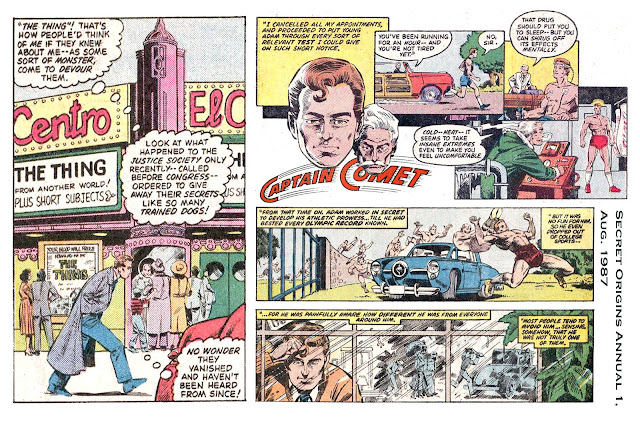

August 1952: Captain Comet, Robot Fighter

When rudely rebuffed by a library

patron who is leafing through books, Adam Blake thinks, “I don’t ordinarily do

this, but I’m going to use my telepathic powers to read his mind.”

Blake discovers that the man is

instantly memorizing every page he sees.

So begins The Brain-Pirates of Planet X in Strange Adventures 23 (Aug. 1952).

Tracing this mental marvel to a

lonely spot in Midwest National Park, Captain Comet and Prof. Zackro find the

man gathering with dozens of duplicates at a spacecraft.

Secretly disabling the ship with

telekinesis, Comet buys enough time to discover that, between them, these

identical men have memorized all the knowledge on Earth.

While the Man of Destiny tracks

down the doppelgängers’ base in space, Zackro phones the Pentagon, saying,

“Captain Comet wants those men held here, General — by armed force if necessary!”

“If Captain Comet wants it, that’s

enough for us, Professor!” the general replies.

Must be nice to be Captain Comet.

Meanwhile, Comet finds a small

world “wrinkled and shrunken… like an old apple” and inhabited by similarly

wrinkled and shrunken ancient green aliens, atrophied into motionlessness, who

are served by robots. They are “science parasites” who absorb the knowledge of

other worlds and then destroy them, deploying suicide robots equipped as

walking nuclear bombs.

The science parasites send their

robot servants against Comet, but he discovers that, like the mythological

giant Antaeus, they are powered by their contact with the floor. Lifting and

smashing the metal men, he leaves the aliens to die unattended.

Flying away in the Cometeer, the Man of Destiny engages in

a little grim self-justification, thinking, “They stole knowledge — destroyed

worlds — with only one purpose — to keep themselves alive — for centuries! They

were evil — and deserved their fate!”

With its relative remorselessness

and preoccupation with the theft of scientific secrets and nuclear destruction

at the hands of an enemy, Brain-Pirates is

a tale that reflects its Cold War origins.

Although the idea of artificial

people dates back at least to the 12th century with the Golem and

the 19th century with Frankenstein, the term “robot” was introduced

in 1920 with the publication of the seminal science fiction play RUR (which stands for Rossumovi

Univerzální Roboti or “Rossum’s Universal

Robots”) by Czech writer Karel Čapek. The story also featured the first

revolt of an enslaved robot population, and the term itself derived from the

Czech word robota, meaning “forced

labor.”

Notable cinematic robots have

included the awesome Gort from The Day

the Earth Stood Still, a film released the year before Strange Adventures 23 appeared, and Robby the Robot, who appeared

in 1956’s Forbidden Planet, 1957’s The Invisible Boy and the 1960s TV

series Lost in Space (alongside the

Robinsons’ Robot, whom he inspired). The

Terminator (1984) and Robocop

(1987) also made their mark.

Famous literary robots include Earl

and Otto Binder’s Adam Link, whose Amazing

Stories adventures appeared from 1939 to 1942, and, of course, Isaac

Asimov’s many robot stories and novels, published from 1940 on. The latter gave

us the very sensible Three Laws of Robotics.

We also had Ray Bradbury’s perfect

grandmother in I Sing the Body Electric, a

1962 Twilight Zone screenplay that

Bradbury turned into a short story. The title comes from a Walt Whitman poem,

which reads in part…

I sing the body electric,

The armies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them,

They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them,

And discorrupt them, and charge them full with the charge of the soul…

…The exquisite realization of health;

O I say these are not the parts and poems of the body only, but of the

soul,

O I say now these are the soul!

Comments

Post a Comment