July 1951: Visions of Future Past

|

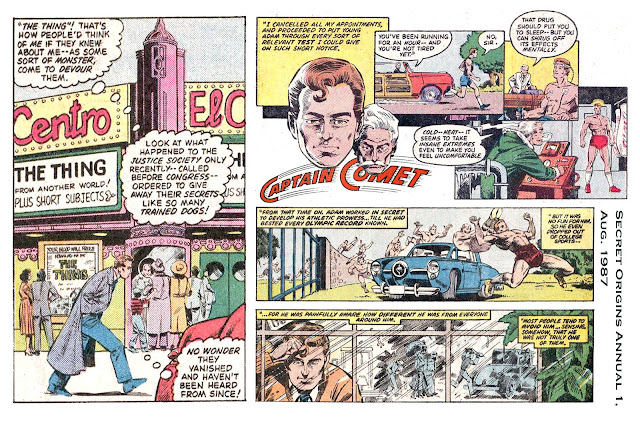

| Strange Adventures 10 finished Captain Comet's two-part origin and launched him on his first adventure. |

Captain Comet blazed the trail in

a feature that looked much more like

1960 than 1940. The sleek elegance of Carmine Infantino’s art was emergent. It

would be contemporary, clean-lined and sunlit, as optimistic and reassuring as

the stories by John Broome.

Infantino made the impossible seem

pleasantly plausible, somehow putting the future within easy reach.

“The mature Infantino drew

everything — a hidden city of scientific gorillas, a harlequin committing

crimes with toys, Flash strapped to a giant boomerang — as if he believed

absolutely in its existence,” observed Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs in their excellent

book The Comic Book Heroes. “But

Infantino’s art could so fully evoke the quiet of a small-town afternoon or the

cool of a shaded lawn that readers could forgive even plots full of beatniks,

schoolteachers and singing idols.”

The equally capable and sunny

Murphy Anderson would illustrate most of Captain Comet’s adventures in his own refined

and deceptively plausible style, beginning in Strange Adventures 12.

Captain Comet was the hero from a vision

of the future now past, a spaceman-superman who designed his own

extraterrestrial vehicle, the Cometeer.

“His super-hero suit was apparently

intended to set the tone for the new, modern, ’50s-style characters,” comics

historian Don Markstein noted. “Instead of the skin-tights of the 1940s super-guys,

he wore a slimmed-down, fancied-up version of an astronaut’s pressure suit —

which, while it hadn’t yet come into use in real life, was already a familiar

sight in sci-fi movies of the time.”

The hero premiered as a cover

feature in a science-fiction anthology title (Strange Adventures 9, June 1951). The tragic note that is played up

explicitly in Superman’s origin has been muted in Comet’s, but is still there

if you look closely enough.

Like Clark Kent, Adam Blake was

raised by kindly Midwestern parents after being displaced — not by light years,

but by millennia.

The boy’s mother didn’t aspire to

greatness for him, but wanted him “…to be just like everyone else.” Her hopes

were dashed when, at age 4, her son’s clairvoyance located her lost ring — the same

trick young Clark Kent performed with his X-ray vision in the 1948 Columbia Superman serial after his foster mother

lost her wristwatch in a haystack.

Blake could recite the entire

contents of books with his photographic memory and instantly play Mozart on the

clarinet. Running touchdowns came easily to a boy who could read the minds of

opposing players.

What wasn’t easy for Blake was

enduring the loneliness of the eternal outsider.

“I’m not like everyone else,” he

thought, brooding one day in college. “I – I try to be, but I’m not! And people

sense it — and avoid me!”

Blake discovered that he was more

different than even he knew when a classmate fell while rock climbing, and he

caught her in midair with mental force.

Consulting physics professor Emery

Zackro, Blake learns his true nature as a kind of anti-throwback, “…an

accidental specimen of future man.”

Confronted by the wonders of Blake’s

“futuristic abilities,” Zackro is given to exclaiming “Great Caesar’s Ghost,”

just as if he were the editor of a great metropolitan newspaper.

Even the hero’s name is subtly

evocative — Adam, the new man, and Blake, the famous visionary.

His birth is marked by the arrival

of a comet, just like that of another American hero with a dual identity, Mark

Twain.

Blake’s occupation as a library

information clerk reflected the reverence for knowledge that would be seen

throughout the Julius Schwartz-edited titles at DC, with their scientist-heroes

and Space Museums. Schwartz’s Silver Age super-heroes would include a police

scientist, an archeologist, a test pilot, a physics professor and a museum

director — all knowledge-based professionals.

Ironically, whether they realized

it or not, fans were seeing into the future of super-hero comics here. Captain

Comet was a hero poised precisely between the Golden and Silver Ages, but

always looking ahead.

The increasingly elegant,

streamlined art and the science fictional themes were among the ingredients

that would converge to spark the Silver Age of Comics five years later, in Showcase 4 (Sept.-Oct. 1956). And

Captain Comet would test-pilot a number of innovative approaches and cover

ideas that would reappear in the Flash, Green

Lantern, Adam Strange and Justice

League of America features.

For example, even in his two-issue

origin and first adventure, Comet faced the menace of gigantic, radiation-emitting

tops that were stealing Earth’s atmosphere. The use of children’s

preoccupations like toy tops as centerpieces would become another familiar Silver

Age plot device, particularly for The Flash’s archenemy the Top.

Seeing radio-magnetic waves

emanating from the moon with his “futuristic eyes,” Comet traces the attack to

a gigantic, thousand-year-old spaceship there, full of tall, light blue aliens

sealed in those transparent tubes that would hold so many captured super-heroes

during the Silver Age.

The Air Bandits from Space turns out to be a surprisingly poignant

story, as Comet learns from the alien leader Harun that his race, the Astur,

are fleeing a dying planet and require an airless world to survive. But Harun,

discovering that his fellow aliens in the tubes are in fact dead, hurls himself

from an airlock in despair, and his now-empty spaceship moves on automatically.

“What irony!” Captain Comet

thinks. “A ship full of dead creatures — searching through the universe for an

ideal world for them to live on!”

Comments

Post a Comment