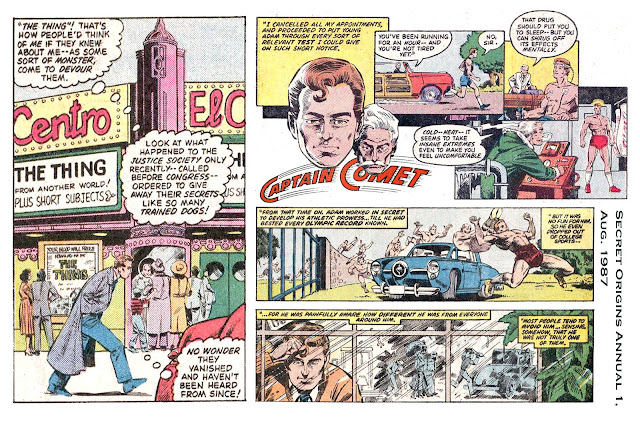

February 1952: Telepathy by Television

The original science fiction

novel, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein,

is the explicit inspiration for Beware

the Synthetic Men! in Strange

Adventures 17 (Feb. 1952).

Rumors of green men in Washington,

D.C., prompt a televised government spokesman to brand them a myth, but Captain

Comet telepathically sees through that lie.

“No reason to fear,” broadcasts

Dr. Stanton, the “nation’s science-defense chief” (didn’t know we had one).

“Great Galaxy!” says Captain

Comet. “He’s saying one thing — thinking the exact opposite!”

For a mutant 100,000 years ahead

of his time, Captain Comet could be remarkably naïve about politics. Or is it

simply that morally and intellectually advanced beings like Adam Blake would

necessarily see the ultimate futility of lying?

“What’s most interesting about this

tale is the use of television,” observed comics historian Michael E. Grost. “One

of Captain Comet’s seemingly endless powers is the ability to read thoughts.

After all, he explains that thoughts are merely electric waves, which his

advanced senses can pick up. But it turns out that thought waves are actually

broadcast by TV, along with the picture and sound, so while watching at home

Captain Comet can read the thoughts of a man who is broadcasting on live TV,

right over the air waves! Green Lantern’s ability to look into people's minds

and see the truth is one of his most important capabilities. Here, Captain

Comet can do something similar.”

Note that in 1945, we had fewer

than 10,000 TV sets in the United States. By 1952, that figure had risen to nearly

17 million.

“Television was so new in 1952

that it was still regarded as an sf invention,” Grost wrote. “It seemed

plausible that it might have undiscovered properties or potentials, such as

thought broadcasting. There are also aspects of social commentary or even

satire here. The story explicitly contrasts what is being said by the

broadcaster to what he is actually thinking. Even in the 1950s, people were

skeptical about this.”

Comet learns the Pentagon’s goal

was to be able to build “synthetic men-warriors who cannot be killed.” The

prototype artificial men, named for the first five letters of the Greek

alphabet, are made of “neoplasm,” which makes them immune to bullets and poison

and gives them super strength.

Mary Shelley’s novel left us with two

enduring themes — one about the creation of artificial life, and the other

about how advancements in knowledge can have unintended and disastrous consequences.

The second comes into play here

when the scaly green super-warriors decide serving human purposes isn’t such a

hot idea. They tear out their prison bars and escape to the countryside,

intending to create a new race of beings.

Tearing down the surrounding

telegraph poles, the green men isolate and seize the small town of Calnit near the

Great Salt Lake.

“Th- they walked through a hail of

bullets!” exclaim the local inhabitants.

“You humans will live — as our

slaves!” the green men reply.

But Captain Comet, knowing that

the synthetics feed on pure calcium nitrate, had reasoned that Calnit might be

one of the places where the green men would hide. With his encyclopedic brain,

Comet was aware that the white oolitic sand near the Great Salt Lake is made up

of concentric layers of calcium carbonate.

Flying to Utah in his rocket ship,

Comet confronted the menace unleashed by what Eisenhower would term the

military-industrial complex.

“Bah! He is human, is he not?”

sneered one of the synthetics. “Therefore bullets will slay him! Fire…”

But although the superhero’s

telekinesis slows the bullets to a harmless speed, he finds his telepathic

powers do not work on the synthetics, who mob him.

Pretending to be overcome, the Man

of Destiny plays for time until he can deduce the green men’s weakness. Then, conspiring

with the townspeople, he traps the synthetics in a small supply room that he

floods with pure oxygen.

“My clue lay in their food —

calcium nitrate,” Comet explains. “Nitrates mean nitrogen and I deduced that it

was the nitrogen in the air which they breathed — not the oxygen! Just as

humans would perish in air of pure nitrogen, so the synthetics couldn’t survive

in pure oxygen! It combined with the calcium in their bodies to form calcium

carbonate — which is the formula for marble!”

Mounted on a hilltop pedestal,

with a plaque, the five frozen beings end up a tourist attraction for Calnit.

The origin of this story can be

traced to the shores of Lake Geneva, Switzerland, on the evening of June 16,

1816, when Lord Byron made a suggestion.

Why not have everybody write a

ghost story?

“Everybody” would include Byron

himself, physician John William Polidori, actress Claire Clairmont, poet Percy

Shelley and his 18-year-old wife Mary.

“Mary Shelley, for her part, could

think of nothing that night — or for several nights thereafter,” noted Peter Haining.

“It seemed as if the whole idea would be a failure.

“Then, unexpectedly, as she lay in

bed about a week later in the half-world between waking and sleeping, Mary

experienced a vivid flight of imagination in which she saw a scientist create

artificial life in a laboratory. Here was her theme, she knew at once, and the

next morning took up her pen.

“The result of that dream was Frankenstein. But not the famous novel

that we know today. Mary, true to the instructions of the challenge, merely

wrote a short story around her nightmare which she then showed to Byron and

Shelley. Her host dismissed it with hardly a glance; her husband, though, read

the few pages rather more carefully, and then declared it was not really a

story. She should perhaps try to turn it into a novel.”

That she did, and the result was

published two years later. “What she also did that night was to give life to

the creature who ever since has walked through all our days and nights and

illustrations and moving pictures…”

And comic books, Haining might have added.

And comic books, Haining might have added.

Comments

Post a Comment