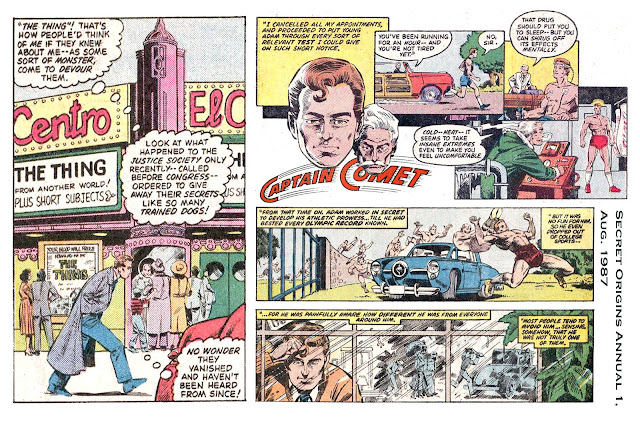

May 1954: Amid the Alien Corn

A Cold War “enemy within” vibe

continues in Strange Adventures 44

(May 1954), when evil, intelligent alien plants disguise themselves as

terrestrial trees.

“Without detection, the aliens landed on Earth — threatening

the very existence of humanity!” proclaims the splash-page narration.

The trees that loom menacingly and

grasp at Captain Comet and his companion Joyce Rollins look a good deal like

the hostile anthropomorphic trees in 1939’s The

Wizard of Oz — a film that CBS would begin airing annually two years later,

on Nov. 3, 1956.

The Plant That Plotted Murder provides another echo of John Wyndham

and his 1951 novel The Day of the

Triffids. The tale anticipates The

Plant That Hated Humans (Strange

Adventures 150, March 1963). That Atomic Knights story — also by John

Broome and Murphy Anderson — features telepathic, malevolent plants.

Cold war fears involving alien

plant life would be famously spotlighted in late 1954 with the serial publication

of Jack Finney’s science fiction novel The

Body Snatchers in Colliers Magazine. Space

seeds drifting to Earth produce pods that perfectly replicate and replace

sleeping human beings — sans emotions. The novel has been filmed four times —

in 1956, 1978, 1993 and 2007.

In Captain Comet’s adventure, an

expeditionary force of Skykarans, whose members disguise themselves as plants,

becomes alarmed by the knowledge that a powerful telepath exists on Earth.

“This Captain Comet must be sought out immediately and destroyed!” the

alien commander Uno mentally proclaims. “Flash the orders to Sectors 3, 4 and 8

… Those nearest to Midwest City. Hurry…”

Meanwhile, the Man of Destiny is

at the Midwest City Daily Clarion,

asking reporter Joyce Rollins about her article concerning a boy who claimed

he’d seen trees walking.

The pair speed to the suburban

scene in the Cometeer as the superhero explains that he’s been “…disturbed by

telepathic impulses which I determined did not arise from members of the animal

kingdom… of which man is a member, of course.”

Attacked by a giant tiger lily,

Comet breaks free with the girl, determined to confront the alien

commander. The two simultaneously

fire ray guns at each other, but neither is harmed.

“Not being able to finish me off

as quickly as he expected seems to have enraged him,” Captain Comet observes.

Brushing against a tree branch,

the angry Uno blasts it, telepathically exclaiming, “Idiot of a mindless

plant!”

The tree topples and crushes him,

and his leaderless task force is quickly routed.

“How ironic,” as they say in the

funny papers.

One nice touch is that the story of

the failed invasion attempt is told entirely in flashback from the enemy point

of view by a “recording thought machine.”

“I have duly recorded all

occurrences that seemed to my control apparatus of the greatest importance in

the invasion!” the device transmits. “But now my energy-spool is running down.

So I must say … farewell! I have done … my duty!”

One of Broome’s distinctive

touches was to sometimes give readers a poignant insight into the feelings of

machines or monsters that might otherwise be incidental to the story. We’ll see

it more than once in his Green Lantern run.

DC was starting to deemphasize

Captain Comet, shifting his feature to the back of the magazine and sometimes

skipping issues.

Inconsistencies began to appear in

the feature, an indication that writers and editors weren’t paying it much

attention any longer — Miss Torrence’s uncertain first name, Blake’s

contradictory relationship with her, Captain Comet’s on-again, off-again secret

identity.

The captain went AWOL in issue 45,

then again in issues 47 and 48. The clock was audibly ticking for Comet, and

not even the Guardians of the Clockwork Universe could do much about it.

Jim Boylan:

ReplyDeleteThey made a movie about one of these plants that hid in a flower store: "Little Shop of Horrors."!

Philip Portelli:

ReplyDeleteI just saw "The Day of the Triffids" (1963). Thought it was okay but slow-paced.

Captain Comet was both ahead of his time and a product of his time. Created during a lull period, he lacked the energy of the latter Schwartz revivals.

I replied:

The novel by John Wyndam is terrific.

Bruce Kanin:

ReplyDeleteWhat a shame that (1) Captain Comet fizzled out, as you wrote, Dan, and (2) his adventures have seemingly not been collected in a graphic novel.